Chasing (Domain) Shadows, a Sisyphean Struggle?

Chances are, if you’re reading this blog post, you know how deeply DNS is rooted in many modern-day security threats. Convincing-looking DNS names are used to trick victims into clicking links in emails or text messages. Random-looking DNS names are used as part of a large attacker infrastructure to evade detection and blocking. Outgoing DNS queries may have sensitive stolen information embedded in them. Incoming DNS answers may carry malicious data to command infected bots to act.

As a result of these DNS abuses, new software features and products have been created to filter or block DNS traffic, much like how the network firewall and web proxies came about to filter or block malicious network and web traffic.

But this is all made possible because you can essentially register any name you want. If you have $9.99 to spare, there’s a domain registrar out there that is willing to sell you a domain name, no matter how shady the name looks.

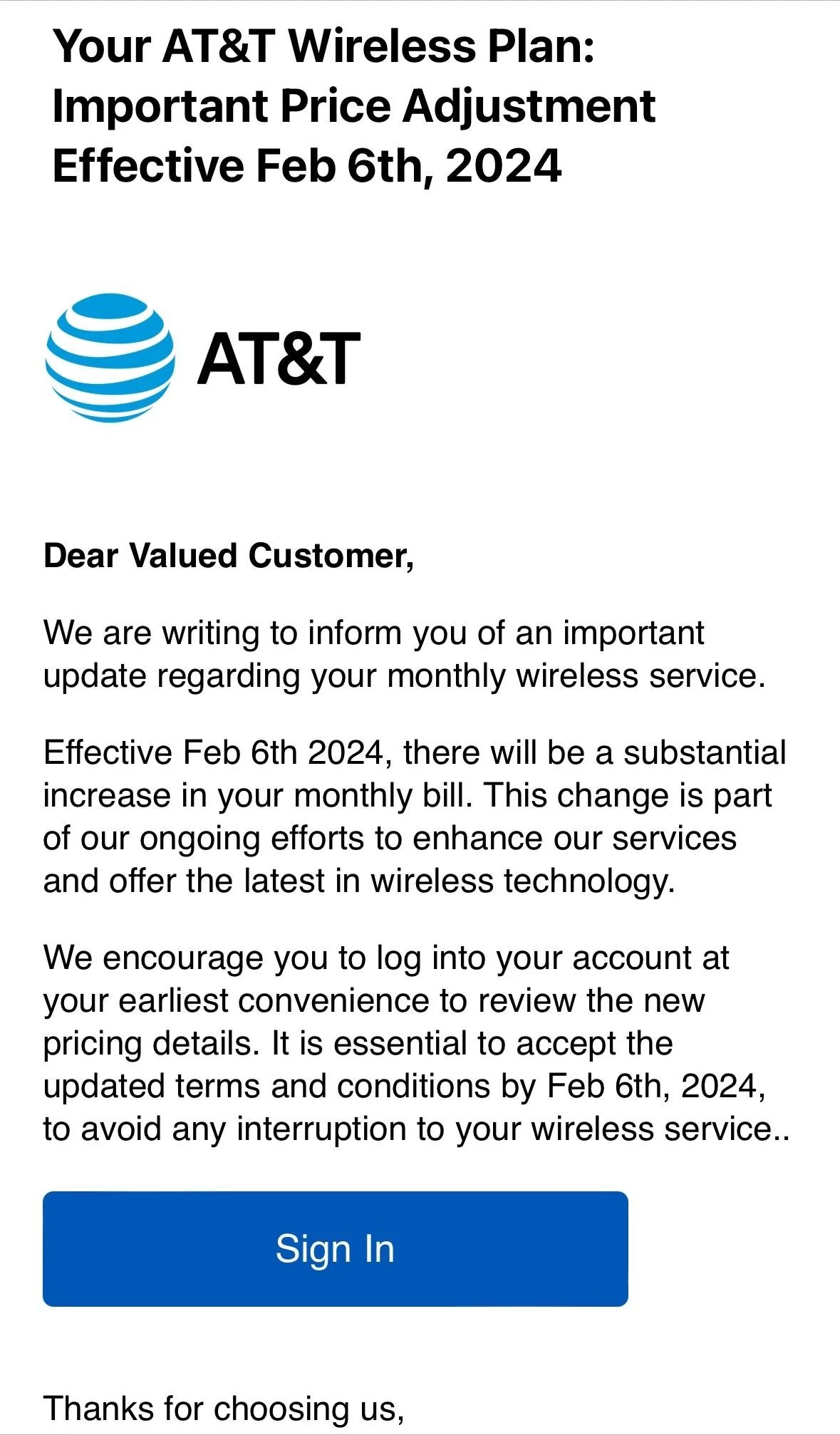

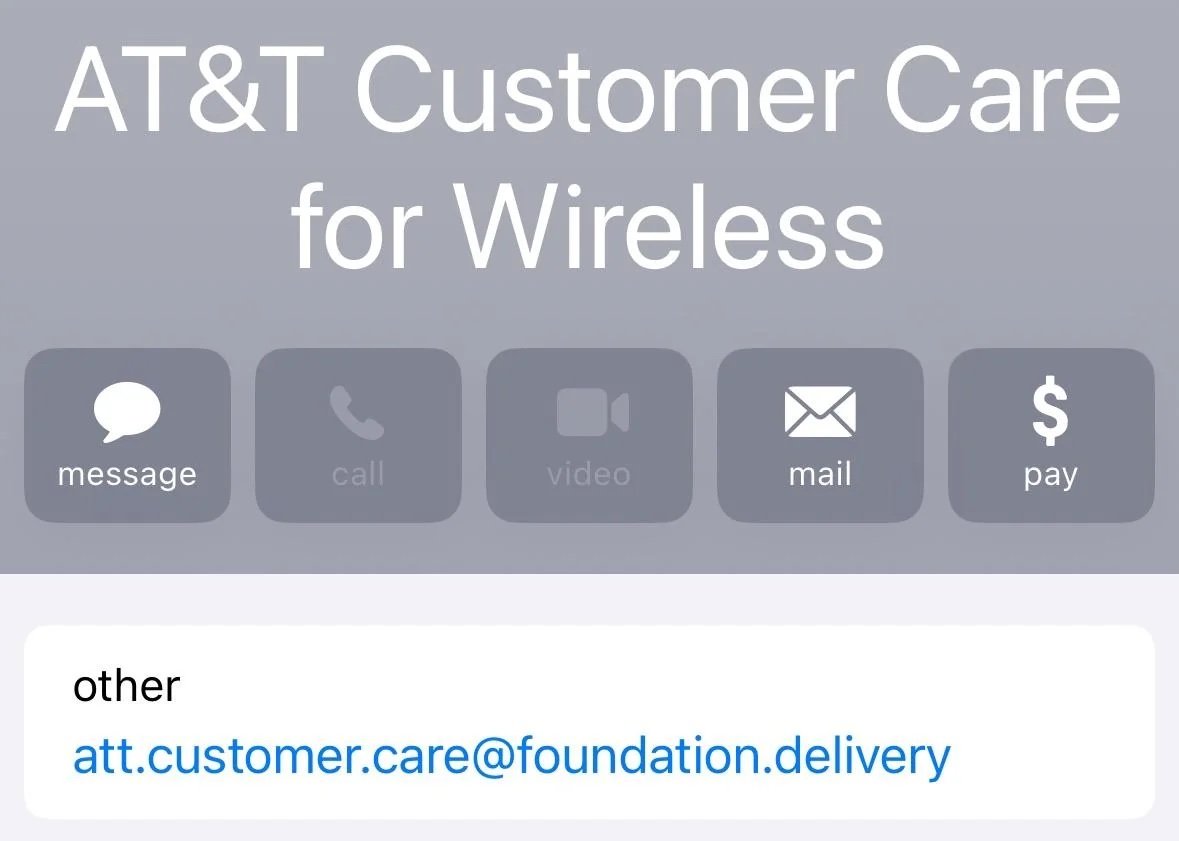

Here is a recent example, a Reddit post from early 2024. I have grabbed the images and posted them below. The Reddit user points out that the message looks authentic, even the email address looks legit. But, this is a phishing scam. One that many people will fall victim to, even those who bothered to look at the sender’s address.

As experienced security professionals, we might be tempted to blame the domain registrar for allowing this name to be registered in the first place. But let’s consider for a second from their point of view: if I am a domain registrar (such as GoDaddy or Hover), when someone wants to pay me $9.99 for a name, how can I tell if this person is doing it with bad intentions?

An easy giveaway would be if the person wants to register a name that looks random, such as 4yxc98bjikaahe11m.com. DNS was invented because we humans are bad at memorizing numbers, so it’s very counterintuitive for someone to register a name that’s harder to remember than an IPv4 address. There is a fairly straightforward way to identify these names by calculating the amount of randomness (i.e. entropy) in the name, using something like the Shannon entropy algorithm. I have described this in more detail in my book “The Hidden Potential of DNS in Security”.

But what if someone wanted to register global-microsoft-customer-service.com? How would I (the registrar) know if this is a legitimate request, from someone who works with Microsoft? In the ideal world, a human would intervene, make contact with the person who wants to register the name, check with the company Microsoft to ensure this request is authorized. However, I am sure we can all agree that is not realistic. What if I spelled Microsoft with an extra letter s? What if I removed the letter t from the end of the name?

These micro (pun intended) decisions make the job of the registrars very difficult. There is no clear solution to preventing these malicious names from being registered in the first place.

So, we come to our second-best solution: filtering them. This directly led to the invention of Response Policy Zone (RPZ) around the year 2014, and that has worked reasonably well for several years. Basically, RPZ allows security researchers to publish a long list of identified/confirmed malicious domain names, and capable DNS servers will filter those names out when anyone asks.

But here’s the catch: this only works if someone CAUGHT your bad domain. What if you were so clever that no one ever discovered your domain name was being used for evil until it’s too late?

Hence, another technique emerged a few years ago, to simply treat every new domain name as a potential threat until they have proven otherwise. A Guilty Until Proven Innocent approach, if you will. I have also discussed this approach at length in my book, covering how each vendor’s approach differ slightly. This technique has a few different names, from Newly Observed Domain, Newly Seen Domain, Newly Registered Domain, to Zero Day DNS.

At the end of the day, this is what we have come to: the Internet has grown into a place where we need to treat everything as hostile or malicious until it has proven NOT to be. This makes me worried about the future of DNS security: are we heading down a path much like the network firewalls, where we block all ports by default and selectively allow benign traffic through? I dread to think of the day that DNS administrators will have to block all domain names by default and only allow the necessary names to resolve.

As we wrap up this dive into the twists and turns of DNS security, it feels like we're in a never-ending chase. Like trying to catch shadows, we're constantly chasing after those elusive domains that harbor threats. But hey, that's the game we're in, right? It's like we're Sisyphus, rolling that boulder up the hill, only to watch it roll back down. But here's the deal: we can't afford to slack off. We've got to keep on our toes, keep innovating, and keep pushing back against the darkness. The good folks at the DNS Abuse Institute are doing exactly that. So, as we keep chasing those domain shadows, let's stay determined. Because in this wild ride, securing the digital world is our mission, and we're not backing down. Here's to staying vigilant, keeping up the chase, and making the internet a safer place, one domain shadow at a time.